Buffer strips: good for growers—and their land

The sun is high in the sky and the temperature is rising on a late summer day in York County. Despite the heat, semiretired farmer Ken Janzen looks perfectly comfortable as he stands on the gravel road next to one of his cornfields. He’s seen plenty of scorching Nebraska weather in his lifetime of farming in this area. Rows of tall green stalks and golden tassels stretch to the horizon in all directions. Amidst the sea of corn, the only sounds are the loud whir of cicadas and the running water of a creek that cuts through Janzen’s property.

It’s the area around the creek that is of special interest today. Janzen points out the wide swath of native grasses that line the banks of the creek. “When we get big rains, the water gets pretty high through here,” he said. Tired of seeing his topsoil washed away down the creek while the banks grew ever steeper with every major rain event, in 2000 Janzen worked with the Upper Big Blue Natural Resources District to take advantage of the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program. Through funds available through the NRD and other state and federal agencies, Janzen was able to receive cost-share funds for the installation of seven acres of native grasses in his fields adjacent to the creek. He also receives an annual payment for those acres to make up for the loss of income involved in taking them out of production.

Buffer strips are native grass or trees planted where runoff water leaves a field. These strips are cultivated along streams, lakes, ponds, or wetlands to protect surface water and reduce erosion. They have many benefits for the land as well as the landowner.

Janzen’s motivation for adding this conservation activity were highly practical. His main concern was his pivots. If he could keep the banks from washing out more and the creek from getting deeper, the pivots were less likely to get stuck when traveling over the creek. He first tried lining the problem areas with concrete, but it wasn’t a good long-term solution. The buffer strips have performed better.

Now when there’s a heavy rain, the grasses are bent over flat for a few days when the water is high, but as soon as the water recedes, the grass bounces back up—and the soil is still where it is supposed to be, Janzen says. When it’s time to irrigate, the pivots are able to cross the small creek without difficulty.

An added benefit is that Janzen can more easily and safely get between the crop and the creek with farm machinery.

Today the water in the creek is low, no more than a slow trickle through the grass. It has been a few weeks since there was a good rain and a pivot is running in a nearby field. The mix of native grasses growing along the creek are waist high. In addition to keeping Janzen’s soil in place, this buffer strip also filters agrochemicals, preventing excess nitrogen from his field from entering the water supply. Janzen likes that he’s doing his part to keep the local waterways clean. According to the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, strips like the ones employed at Janzen’s farm can filter up to 60 percent of pesticides and can remove up to 75 percent of sediment from entering the creek.

“We know that vegetative filter strips and riparian forest buffer strips positively impact water quality by reducing the amount of sediment, pesticides, and nutrients that reach surface water,” said Craig Romary, environmental programs specialist with the Nebraska Department of Agriculture. “These practices are just a part of many other best management practices that are being implemented in an effort to keep sediment and other contaminants from leaving the farm.”

This kind of common-sense conservation is a no-brainer for Nebraska, says Romary. “Reducing nonpoint source pollution to our surface waters benefits all Nebraskans.”

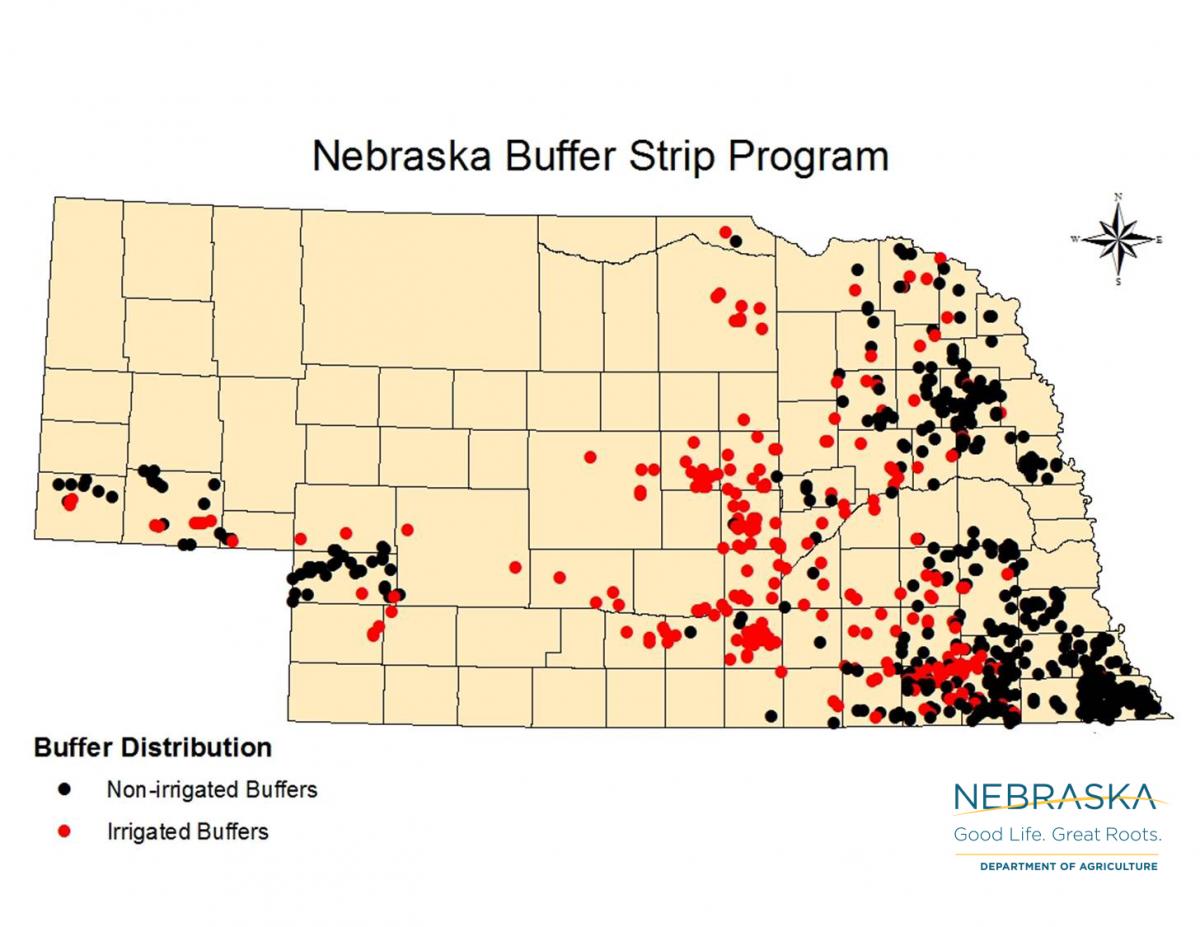

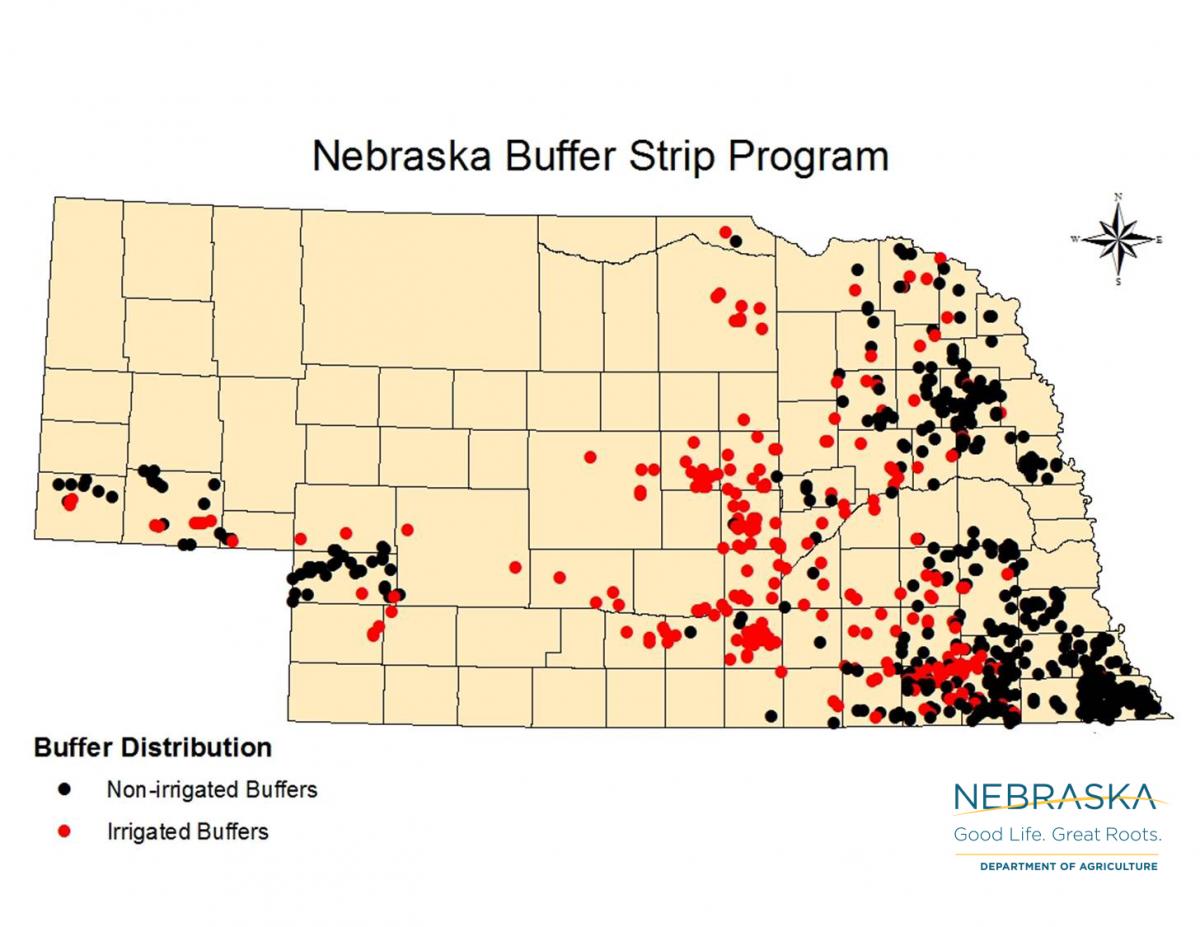

Janzen is one of 428 producers in the state who are part of the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program, which currently has 3,889 acres enrolled. The program began in 1999 and Janzen was an early adopter. Annually, the program pays out nearly $600,000 to Nebraska landowners for their participating acres.

In the Upper Big Blue NRD, there are 23 contracts for about 170 acres of filter strips with an annual payout of more than $30,000. These filter strips provide protection for approximately 21 miles of streambanks.

“Buffer strips were one of the priority practices identified by the Stakeholder Advisory Committee during the development of the district wide Water Quality Management Plan,” noted Jack Wergin, projects department manager at the Upper Big Blue NRD. Two segments of Beaver Creek were identified as priority waterbodies in this plan, which resulted in the entire Beaver Creek drainage area being named as a single target area.

“The Water Quality Management Plan serves as a roadmap to improve the water resources and water quality within the district. As we begin the implementation phase, we hope to see an increase in the number of buffer strips, especially in the targeted priority areas around Beaver Creek.”

Janzen encourages other producers to consider adding buffer strips to their operations, especially in low-lying areas that are prone to flooding. “It’s a good way to keep the soil in your field and control erosion--and you get paid pretty well for the acres,” he said. Without the strips, Janzen noted that he would be losing money and topsoil every year on the harder to farm stretch of land. The conservation practice has proven to be good for the environment and very good for his wallet over the past 20 years.

Contracts with producers in the program last five to ten years and payments vary from $20 to $250 per acre depending on soil type, whether the areas are irrigated or not, and whether payments are received from other programs. The program can be partnered with the USDA Conservation Reserve Program for additional incentives.

The 95-year-old house where Janzen grew up is nearby. Built by his grandparents, it’s also where Janzen’s mother grew up. Today, his son’s family lives there and farms the land with him. His grandson, representing the fifth generation of Janzens on the property, drives a pedal tractor around the outbuildings as the farm dogs keep watch. Another section of buffer strip lines a small creek between the home place and the gravel road. While Janzen is looking forward to retiring fully someday, he’s committed to leaving his son, grandson, and future generations of Janzens a farming operation that is in the best shape possible. Conservation practices like buffer strips are part of that plan.

Harvest is a great time to evaluate your fields and see if a buffer strip should be added in the coming year. For more information on how you can participate in the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program, contact the NRD at 402-362-6601, your local county NRCS office, or visit http://bit.ly/NDAbuffer.

The photos below show a buffer strip in action in a field in Nebraska. The top photo is taken during the storm and the second photo is shortly after. The buffer strip helps control the water flow and protects the soil from being washed out.

It’s the area around the creek that is of special interest today. Janzen points out the wide swath of native grasses that line the banks of the creek. “When we get big rains, the water gets pretty high through here,” he said. Tired of seeing his topsoil washed away down the creek while the banks grew ever steeper with every major rain event, in 2000 Janzen worked with the Upper Big Blue Natural Resources District to take advantage of the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program. Through funds available through the NRD and other state and federal agencies, Janzen was able to receive cost-share funds for the installation of seven acres of native grasses in his fields adjacent to the creek. He also receives an annual payment for those acres to make up for the loss of income involved in taking them out of production.

Buffer strips are native grass or trees planted where runoff water leaves a field. These strips are cultivated along streams, lakes, ponds, or wetlands to protect surface water and reduce erosion. They have many benefits for the land as well as the landowner.

Janzen’s motivation for adding this conservation activity were highly practical. His main concern was his pivots. If he could keep the banks from washing out more and the creek from getting deeper, the pivots were less likely to get stuck when traveling over the creek. He first tried lining the problem areas with concrete, but it wasn’t a good long-term solution. The buffer strips have performed better.

Now when there’s a heavy rain, the grasses are bent over flat for a few days when the water is high, but as soon as the water recedes, the grass bounces back up—and the soil is still where it is supposed to be, Janzen says. When it’s time to irrigate, the pivots are able to cross the small creek without difficulty.

An added benefit is that Janzen can more easily and safely get between the crop and the creek with farm machinery.

Today the water in the creek is low, no more than a slow trickle through the grass. It has been a few weeks since there was a good rain and a pivot is running in a nearby field. The mix of native grasses growing along the creek are waist high. In addition to keeping Janzen’s soil in place, this buffer strip also filters agrochemicals, preventing excess nitrogen from his field from entering the water supply. Janzen likes that he’s doing his part to keep the local waterways clean. According to the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, strips like the ones employed at Janzen’s farm can filter up to 60 percent of pesticides and can remove up to 75 percent of sediment from entering the creek.

“We know that vegetative filter strips and riparian forest buffer strips positively impact water quality by reducing the amount of sediment, pesticides, and nutrients that reach surface water,” said Craig Romary, environmental programs specialist with the Nebraska Department of Agriculture. “These practices are just a part of many other best management practices that are being implemented in an effort to keep sediment and other contaminants from leaving the farm.”

This kind of common-sense conservation is a no-brainer for Nebraska, says Romary. “Reducing nonpoint source pollution to our surface waters benefits all Nebraskans.”

Janzen is one of 428 producers in the state who are part of the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program, which currently has 3,889 acres enrolled. The program began in 1999 and Janzen was an early adopter. Annually, the program pays out nearly $600,000 to Nebraska landowners for their participating acres.

In the Upper Big Blue NRD, there are 23 contracts for about 170 acres of filter strips with an annual payout of more than $30,000. These filter strips provide protection for approximately 21 miles of streambanks.

“Buffer strips were one of the priority practices identified by the Stakeholder Advisory Committee during the development of the district wide Water Quality Management Plan,” noted Jack Wergin, projects department manager at the Upper Big Blue NRD. Two segments of Beaver Creek were identified as priority waterbodies in this plan, which resulted in the entire Beaver Creek drainage area being named as a single target area.

“The Water Quality Management Plan serves as a roadmap to improve the water resources and water quality within the district. As we begin the implementation phase, we hope to see an increase in the number of buffer strips, especially in the targeted priority areas around Beaver Creek.”

Janzen encourages other producers to consider adding buffer strips to their operations, especially in low-lying areas that are prone to flooding. “It’s a good way to keep the soil in your field and control erosion--and you get paid pretty well for the acres,” he said. Without the strips, Janzen noted that he would be losing money and topsoil every year on the harder to farm stretch of land. The conservation practice has proven to be good for the environment and very good for his wallet over the past 20 years.

Contracts with producers in the program last five to ten years and payments vary from $20 to $250 per acre depending on soil type, whether the areas are irrigated or not, and whether payments are received from other programs. The program can be partnered with the USDA Conservation Reserve Program for additional incentives.

The 95-year-old house where Janzen grew up is nearby. Built by his grandparents, it’s also where Janzen’s mother grew up. Today, his son’s family lives there and farms the land with him. His grandson, representing the fifth generation of Janzens on the property, drives a pedal tractor around the outbuildings as the farm dogs keep watch. Another section of buffer strip lines a small creek between the home place and the gravel road. While Janzen is looking forward to retiring fully someday, he’s committed to leaving his son, grandson, and future generations of Janzens a farming operation that is in the best shape possible. Conservation practices like buffer strips are part of that plan.

Harvest is a great time to evaluate your fields and see if a buffer strip should be added in the coming year. For more information on how you can participate in the Nebraska Buffer Strip Program, contact the NRD at 402-362-6601, your local county NRCS office, or visit http://bit.ly/NDAbuffer.

The photos below show a buffer strip in action in a field in Nebraska. The top photo is taken during the storm and the second photo is shortly after. The buffer strip helps control the water flow and protects the soil from being washed out.